Introduction: The Fight For Worker’s Rights

The Battle of Blair Mountain remains a major historical event that helped forge a path for better working conditions among mine workers. Although conditions have improved, the fight continues today for safe working conditions and fair treatment for workers across the country. The Battle of Blair Mountain took place in 1920, but the events that led up to this pivotal moment extend back to 1912. Unfair wages, hunger, and poor working conditions all attributed to the events that follow.2

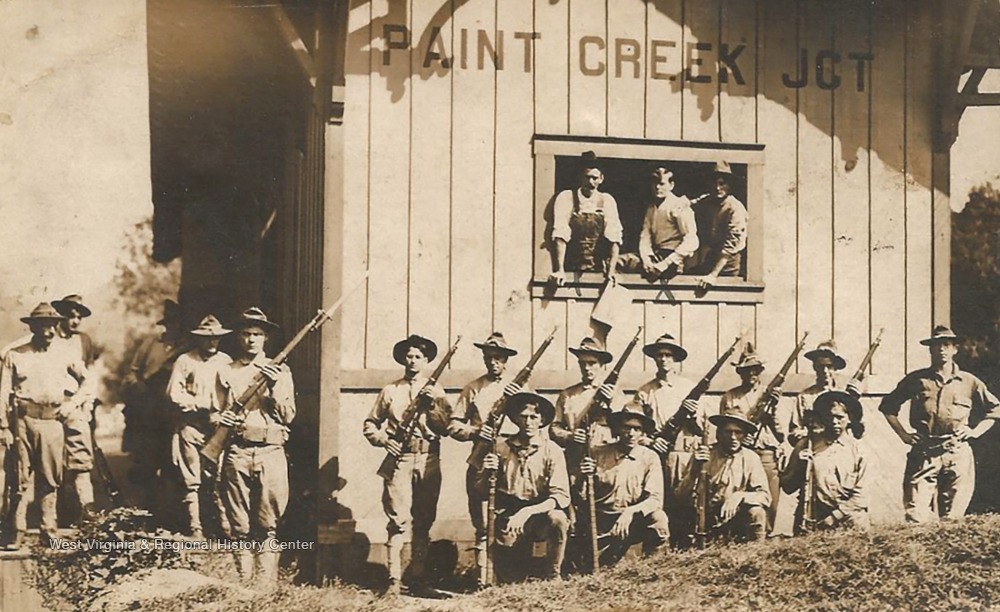

The Paint Creek-Cabin Creek Strike of 1912

Cabin Creek, West Virginia3

The escalating tensions that led to Blair Mountain were not spontaneous; they were rooted in years of unresolved conflict, starting in the Kanawha Coalfield with the Paint Creek-Cabin Creek Strike of 1912.3

The Fight for a Voice

The miners’ demands were simple: the right to unionize under the UMWA and the end of exploitative practices. Union organizer Mary “Mother” Jones and UMW vice president Frank Hayes were sent to help the strikers. The coal operators’ response was immediate: they hired over 300 agents from the notorious Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency to end the strike by force. With little resistance from the local government, these agents were deputized, transforming them from private thugs into figures of state authority.3

- Baldwin-Felts guards evicted striking families from company housing, forcing them to live in freezing tent colonies established by the UMWA.

- The guards maintained control by constructing forts armed with machine guns, blocking miners from using public bridges and trains, and beating anyone who attempted to leave. This created an atmosphere of complete siege.

The “Bull Moose Special” (February 7, 1913)

The conflict reached a shocking climax on February 7. Coal operator Quinn Martin and Sheriff Bonner Hill drove an improvised armored train, dubbed the “Bull Moose Special,” through the Holly Grove tent colony, firing indiscriminately into the tents and homes of sleeping families.

During the attack, Italian miner Francis Francesco Estep was tragically shot and killed while attempting to protect his pregnant wife. This single, brazen act of violence by agents of the coal company cemented the miners’ conviction: they were at war.3

Martial Law and Moral Outrage

Fighting paused when Governor William E. Glasscock declared martial law. While miners initially welcomed the militia, hoping for peace, the Governor’s true intent quickly became apparent. The militia acted solely to break the strike, arresting over 200 strikers and strike leaders, including the revered “Mother” Jones, without warrants. Crucially, the Baldwin-Felts agents and coal operators faced no consequences for their actions.

This biased execution of martial law was condemned across the country and established a grim precedent: in West Virginia’s southern coalfields, the law itself was a tool of corporate control. This cycle of violence and impunity is the powder keg that would later explode in Matewan.4

The Matewan Massacre and the Road to War

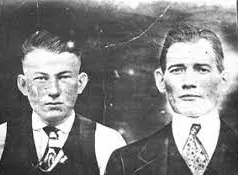

Deputy Ed Chambers (Right)5

The brutality witnessed at Paint Creek had established a violent pattern, but the conflict reached its breaking point when it moved to the incorporated town of Matewan, West Virginia. Unlike the surrounding coal camps where operators were the absolute law, Matewan had an elected government, led by the defiant Police Chief Sid Hatfield. Hatfield, sympathetic to the union, was determined to protect his citizens from corporate tyranny.6

The Matewan Massacre (May 19, 1920)

The confrontation was swift and tragic. On May 19, 1920, a squad of Baldwin-Felts agents arrived in Matewan with orders to evict union-affiliated miners and their families from company housing. As the agents prepared to carry out the evictions, Sheriff Hatfield attempted to serve them arrest warrants.

The ensuing argument escalated into a massive, chaotic street gunfight. When the smoke cleared, seven Baldwin-Felts agents were dead, including the agency’s leaders, brothers Albert and Lee Felts. The mayor of Matewan, Cabell Testerman, was also killed during this shootout. The miners hailed Hatfield as a hero who had finally stood up to corporate power. Though Hatfield was charged with murder, he was later acquitted by a local jury. For the coal operators, this verdict was a profound, intolerable defeat.6

The Assassination (August 1, 1921)

The victory was short-lived. Just over a year after his acquittal, Hatfield and his deputy, Ed Chambers, traveled to the McDowell County Courthouse to face charges unrelated to the shootout.

As the two men ascended the courthouse steps, they were ambushed and shot to death in broad daylight by Baldwin-Felts agents. The murder of the popular union hero, committed with such brazen impunity, shattered the miners’ faith in the legal system. The news of Hatfield’s martyrdom spread like wildfire, confirming to the miners that the operators were above the law and that armed self-defense was the only option left.

The assassination of Sid Hatfield was the direct catalyst that mobilized over ten thousand miners to arm themselves and begin their famous march toward Logan County.6

The Battle of Blair Mountain

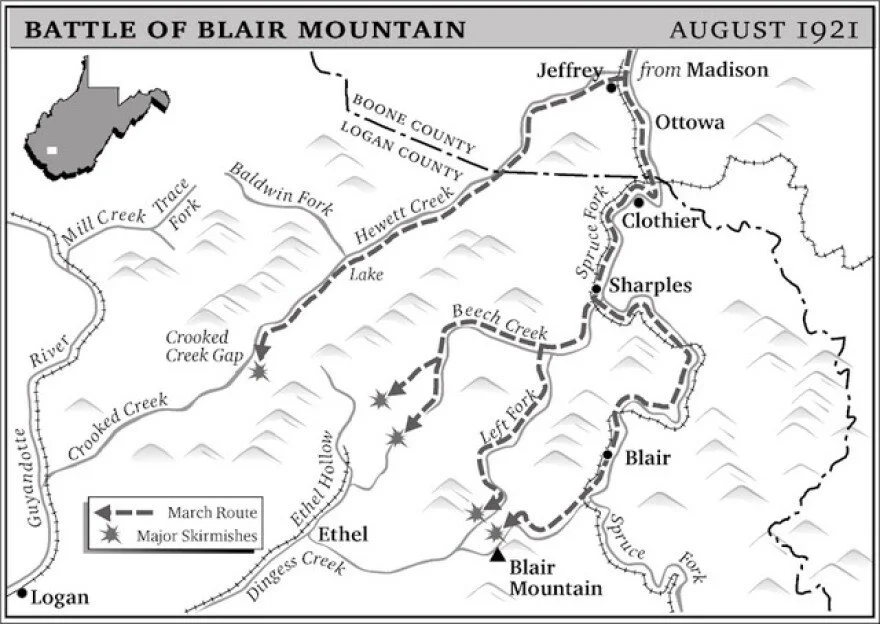

Battle of Blair Mountain

Charleston Gazette, 10 September 19217

The murder of Sheriff Hatfield was the final straw. It shattered the miners’ faith in the legal process and pushed them into action. News of the assassination mobilized over ten thousand armed miners who streamed from the southern coalfields, forming a massive, makeshift miners’ army (often called the “redneck army”). Their objective was clear: march south to Logan and Mingo counties to forcibly end the corporate rule that protected the Baldwin-Felts agents, unionize the coalfields, and free the imprisoned union strikers.8

The Private Army

The miners’ march met its opposition at Blair Mountain from a massive private defense force organized by Sheriff Don Chafin of Logan County. Chafin, notorious for his corruption and absolute control by the coal operators, had amassed a private army composed of thousands of deputies, coal guards, and vigilantes. They fortified the ridges of Blair Mountain with trenches and machine-gun nests, creating a formidable barrier.8

Aerial Bombing and War

The two armies clashed fiercely along the ridges. The fighting lasted several days, escalating the conflict far beyond a simple labor dispute. In a truly shocking display of corporate power, Don Chafin’s forces utilized aircraft—biplanes—to drop pipe bombs and tear gas onto the miners below . This marked one of the few instances in U.S. history where private citizens were bombed by private forces on American soil.8

Federal Intervention and Surrender

The extreme violence forced the federal government to intervene. President Warren G. Harding ordered the deployment of U.S. Army troops and federalized National Guard units. Bill Blizzard, the main field commander for the miners, understood the implications of fighting the federal government. To prevent further bloodshed and to demonstrate the loyalty of the miners, he gave the order to surrender. The largest armed labor uprising in U.S. history ended not with a defeat by the coal operators, but with the peaceful surrender of the miners to the U.S. Army.9

The Aftermath: Treason Trials

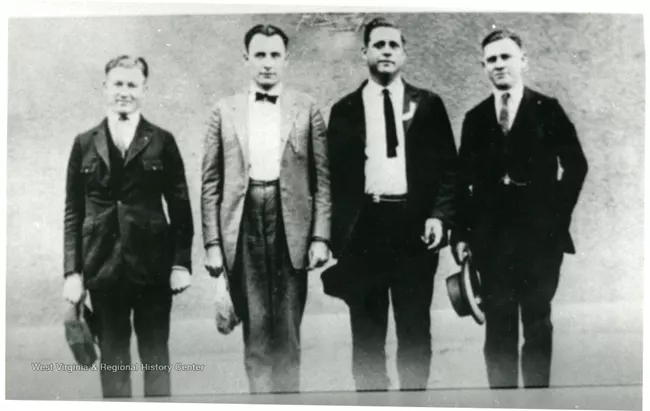

Bill Blizzard, Fred Mooney, William Petry, Frank Keeney10

The surrender of the miners to the U.S. Army on Blair Mountain brought the armed conflict to an end, but it launched the most significant legal battle in American labor history. The state quickly arrested hundreds of miners, eventually charging 985 miners with various crimes, with the most serious being treason against the State of West Virginia. The state’s goal was to not only punish the participants but to crush the union movement permanently.12

The Trial of Bill Blizzard

The state’s main target was Bill Blizzard, the miners’ field commander. His trial for treason was a dramatic courtroom showdown that captured national attention. The defense attorney, T.C. Townsend, mounted a brilliant counter-argument: the miners were not committing treason against the government. Instead, they were acting in necessary self-defense against a corrupt, heavily armed private army led by Sheriff Don Chafin, who was illegally using his badge to enforce corporate greed.

The jury ultimately sided with the miners. Blizzard was acquitted (found not guilty). This verdict was a massive moral and legal victory, as it effectively shattered the state’s treason case against the hundreds of other miners.11

The Unfinished Business

While the miners won the legal battle and gained crucial momentum for unionization efforts, the fundamental problems of corporate control and worker fear persisted in the southern non-union coalfields. The battle demonstrated the miners’ fierce resolve, but the economic silence—the fear of job loss, the poor conditions, and the lack of a voice—remained.

This struggle, born in the violence of Paint Creek and climaxing on Blair Mountain, created an unfinished legacy—one that is tragically evident in the modern crises miners face today.12

Conclusion: The Fight Continues

The Battle of Blair Mountain ended not with a bang, but with a peaceful surrender to the U.S. Army. The subsequent acquittal of union leader Bill Blizzard on treason charges was a massive legal and moral victory. It proved that the union cause had merit and began a wave of organizing that would eventually bring union representation and better conditions to the coalfields.

However, the legacy of Blair Mountain remains an unfinished business. While the violence of the Baldwin-Felts agents has passed, the miners’ fundamental struggle for basic human safety continues.

Today, that fight is against an invisible enemy: silica dust, which causes the aggressive resurgence of Black Lung disease. Just as the miners of 1921 fought for control over their lives, modern advocates and miners are fighting corporate and political forces to enforce protective regulations. When safety measures—like the crucial silica dust rule—are delayed or blocked, it sends a message chillingly similar to the one sent by the armored train at Paint Creek: profit takes precedence over the lives of the workers.13

The miners who marched on Blair Mountain risked everything for the principle that no person should have to sacrifice their health or safety for a paycheck. Their sacrifice is a constant reminder: the struggle for worker’s rights isn’t just history; it’s a daily battle for safety and dignity that continues on the mountains of West Virginia and across the country today.

Sources:

- WV Humanities Council

↩︎ - https://umwa.org/about/history/

Wayback Machine link: https://web.archive.org/web/20250424120202/https://umwa.org/about/history/

https://westvirginiawatch.com/2025/08/14/they-dont-care-advocates-for-miners-with-black-lung-worry-as-silica-dust-rule-delayed-again/

Wayback Machine link: https://web.archive.org/web/20250910161952/https://westvirginiawatch.com/2025/08/14/they-dont-care-advocates-for-miners-with-black-lung-worry-as-silica-dust-rule-delayed-again/

↩︎ - https://wvhistoryonview.org/catalog/045093

↩︎ - https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/paint-creek-and-cabin-creek-strikes.htm

Wayback Machine link: https://web.archive.org/web/20251006172310/https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/paint-creek-and-cabin-creek-strikes.htm

↩︎ - Howard B. Lee Papers, Marshall University Archives and Special Collections.

↩︎ - https://wvminewars.org/news/battleofblair

Wayback Machine link: https://web.archive.org/web/20250318055352/https://wvminewars.org/news/battleofblair

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Blair_Mountain

Wayback Machine link: https://web.archive.org/web/20251008052944/https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Blair_Mountain

↩︎ - https://archive.wvculture.org/history/labor/mwnews.html

↩︎ - https://expatalachians.com/biplanes-over-blair-calling-in-the-air-force-for-the-mine-wars

Wayback Machine link: https://web.archive.org/web/20250806114834/http://expatalachians.com/biplanes-over-blair-calling-in-the-air-force-for-the-mine-wars

↩︎ - https://wvminewars.org/news/battleofblair

Wayback Machine link: https://web.archive.org/web/20250318055352/https://wvminewars.org/news/battleofblair

↩︎ - West Virginia & Regional History Center

↩︎ - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Blair_Mountain

Wayback Machine link: https://web.archive.org/web/20251008052944/https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Blair_Mountain

↩︎ - https://web.archive.org/web/20220818131556/http://coalheritage.org/page.aspx?id=53

↩︎ - https://westvirginiawatch.com/2025/08/14/they-dont-care-advocates-for-miners-with-black-lung-worry-as-silica-dust-rule-delayed-again/

Wayback Machine link: https://web.archive.org/web/20250910161952/https://westvirginiawatch.com/2025/08/14/they-dont-care-advocates-for-miners-with-black-lung-worry-as-silica-dust-rule-delayed-again/

↩︎